DEM20101541

Emanuela Borgia

Abstract

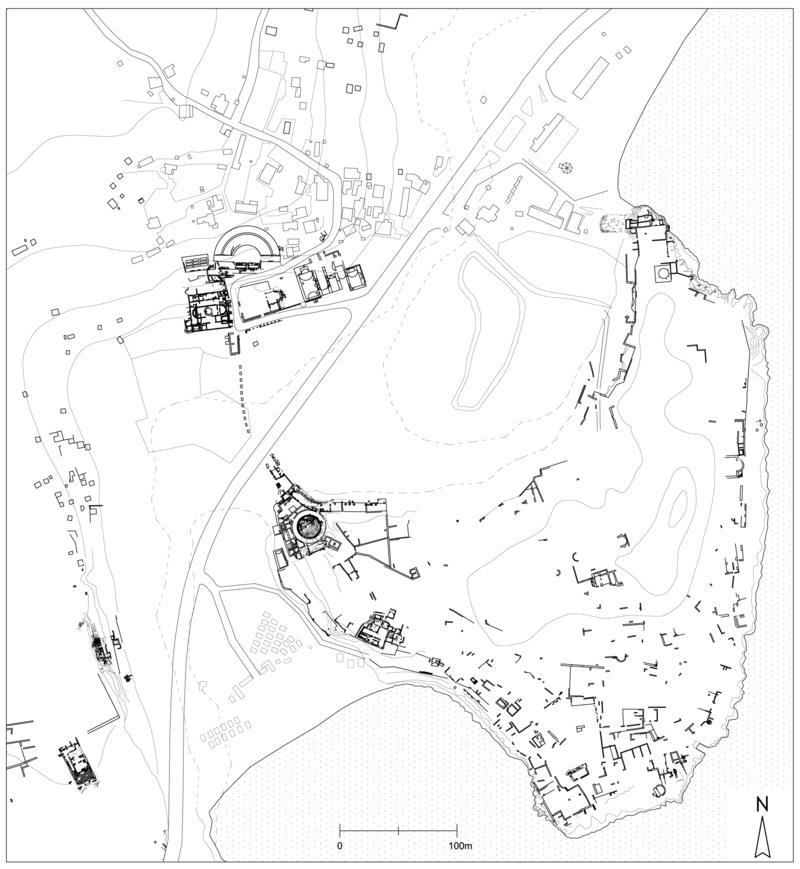

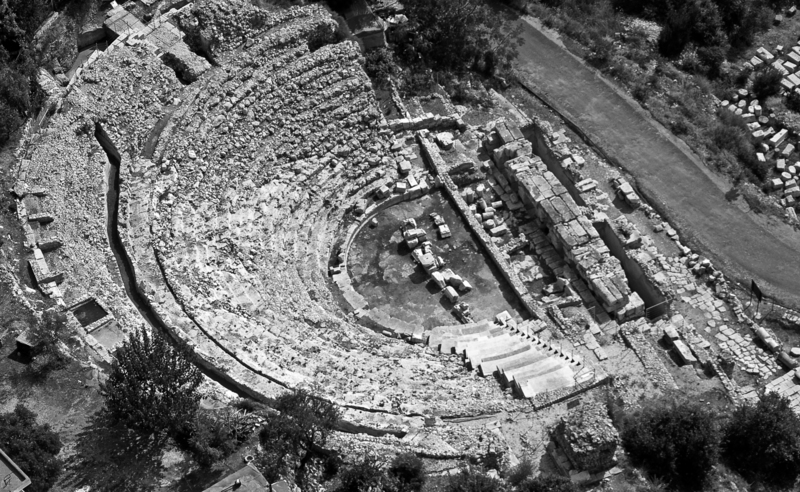

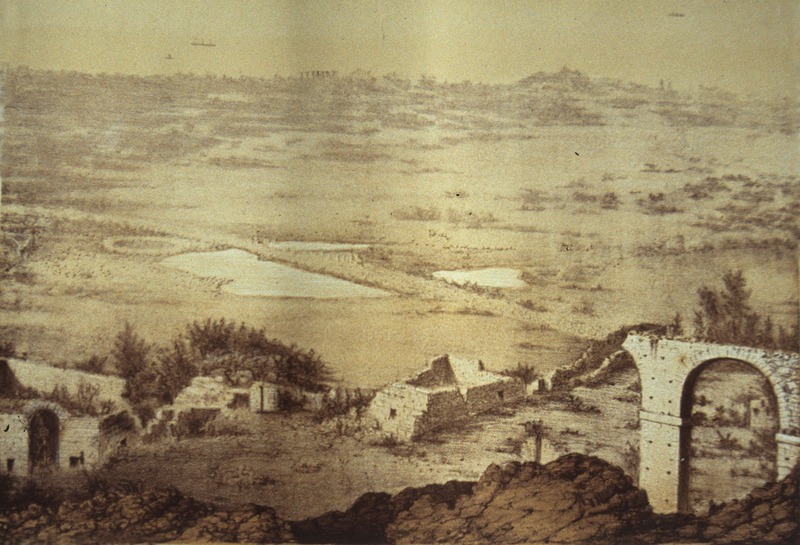

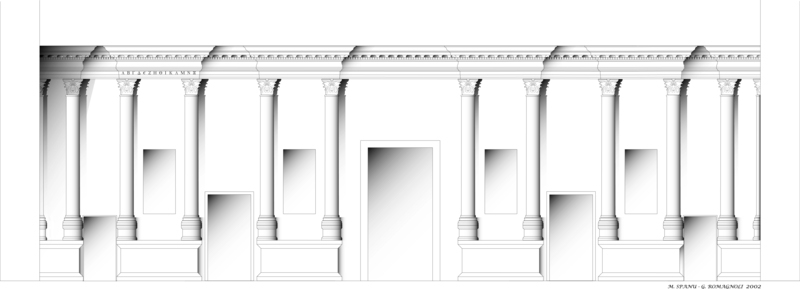

Il teatro romano di Elaiussa Sebaste, indagato estensivamente negli anni 1995-1999, fu realizzato sulle pendici meridionali della collina che si affaccia sul porto settentrionale della città e rientra in un più vasto programma architettonico cui appartengono anche l’Agora e le Grandi Terme. I dati archeologici consentono di datare la costruzione dell’edificio attorno alla metà del II sec. d.C., con un importante rifacimento dell’edificio scenico durante il regno di Marco Aurelio. Il teatro era parzialmente in rovina già alla fine del III o nei primi anni del IV sec. d.C., epoca in cui però le cisterne meridionali e l’acquedotto erano ancora in funzione. Il complesso fu completamente abbandonato a partire dal V sec. d.C. e, nel VII secolo subì una sistematica operazione di spoliazione. Le indagini archeologiche hanno consentito di delineare le fasi di vita precedenti alla realizzazione del teatro. Tra la fine del I sec. a.C. e il I sec. d.C. l’area si trovava ai limiti dell’insediamento ed era occupata da una necropoli con tombe rupestri ricavate ai piedi della collina. Probabilmente durante il I sec. d.C. fu costruito anche l’acquedotto urbano, che correva da est ad ovest con andamento rettilineo a mezza costa. Verso la fine del I o agli inizi del II sec. d.C. sulla collina fu costruito un complesso residenziale con terme private, di cui sono stati individuati solo alcuni vani nel settore del vomitorium orientale: l’edificio fu infatti distrutto e rasato al momento della costruzione del teatro. Un accurato riesame dei resoconti dei viaggiatori che visitarono la Cilicia tra il XIX e la prima metà del XX secolo (tra cui Sir F. Beaufort, C.L. Irby e J. Mangles, V. Langlois, P. Trémaux, R. Heberdey e A. Wilhelm, R. Paribeni e P. Romanelli, J. Keil e A. Wilhelm, M. e M. Gough) ed alcuni dati inediti reperiti negli archivi della Kleinasiatische Kommission der Wiener Akademie der Wissenschaften (Wien), nel G.L. Bell Archive (Newcastle upon Tyne) e nell’archivio del British Institute at Ankara forniscono un importante contributo per la conoscenza della storia recente del monumento. Le descrizioni dei viaggiatori e le prime foto del teatro, opera di G. L. Bell (1905), consentono di comprendere che il teatro era già allora piuttosto mal conservato, privo della decorazione e di tutti i sedili, mentre le alae erano indubbiamente meglio conservate. Per quanto concerne in particolare l’articolazione dell’edificio, esso ha una pianta maggiore del semicerchio, con diametro di m. 55. La maggior parte della cavea, ripartita in cinque cunei da sei scalaria, è tagliata nel banco roccioso naturale, mentre la summa cavea e le alae sono costruite in cementizio con paramento in opera quadrata, visibile in corrispondenza degli analemmata e del muro esterno. La praecinctio mediana divide l’auditorio in ima cavea (con quindici file di sedili) e summa cavea (con cinque file); a monte della praecinctio corre il canale dell’acquedotto, che fu trasformato assumendo un andamento curvilineo al momento della costruzione della cavea. L’accesso all’edificio per spettacoli era garantito da due vomitoria asimmetrici e dalle due parodoi scoperte. Adiacente al vomitorium occidentale è il castellum aquae a pianta circolare, che rimase in uso fino al V sec. d.C., come hanno dimostrato recenti ricerche (2006).

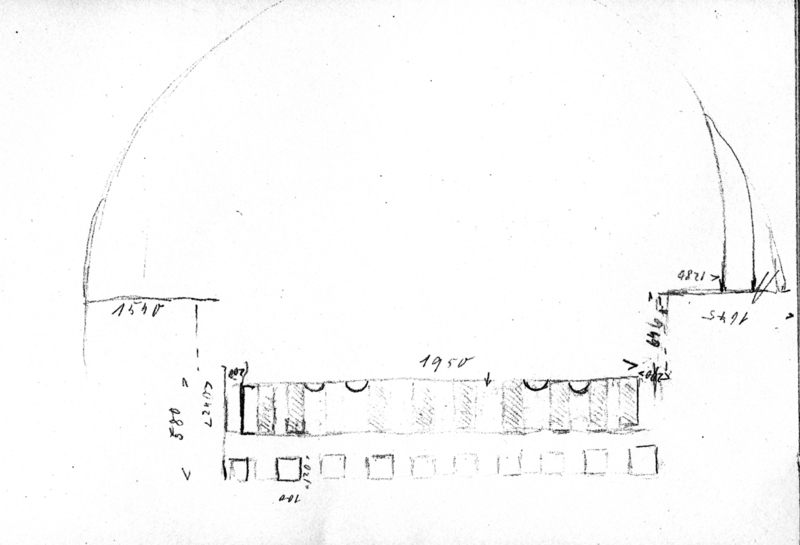

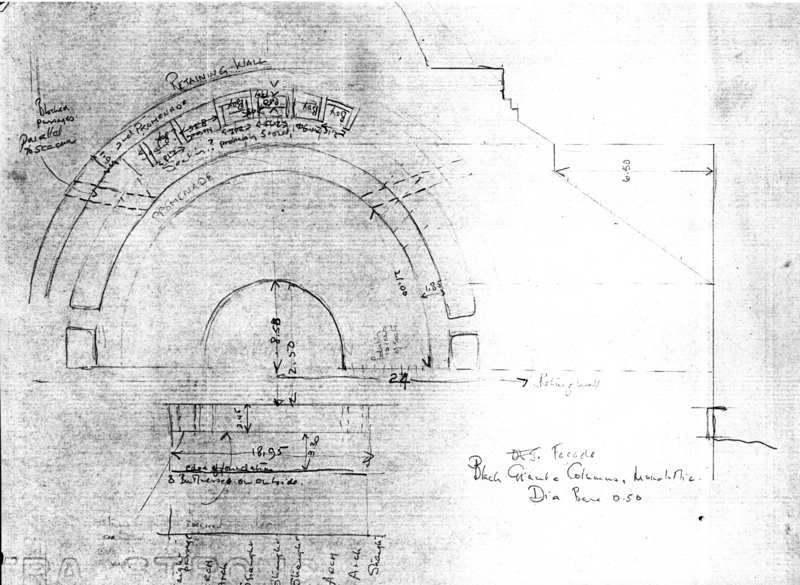

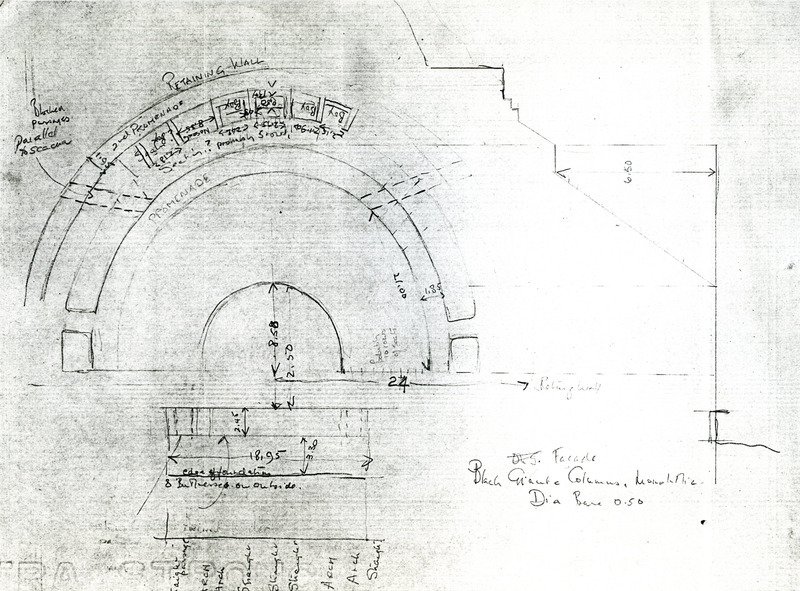

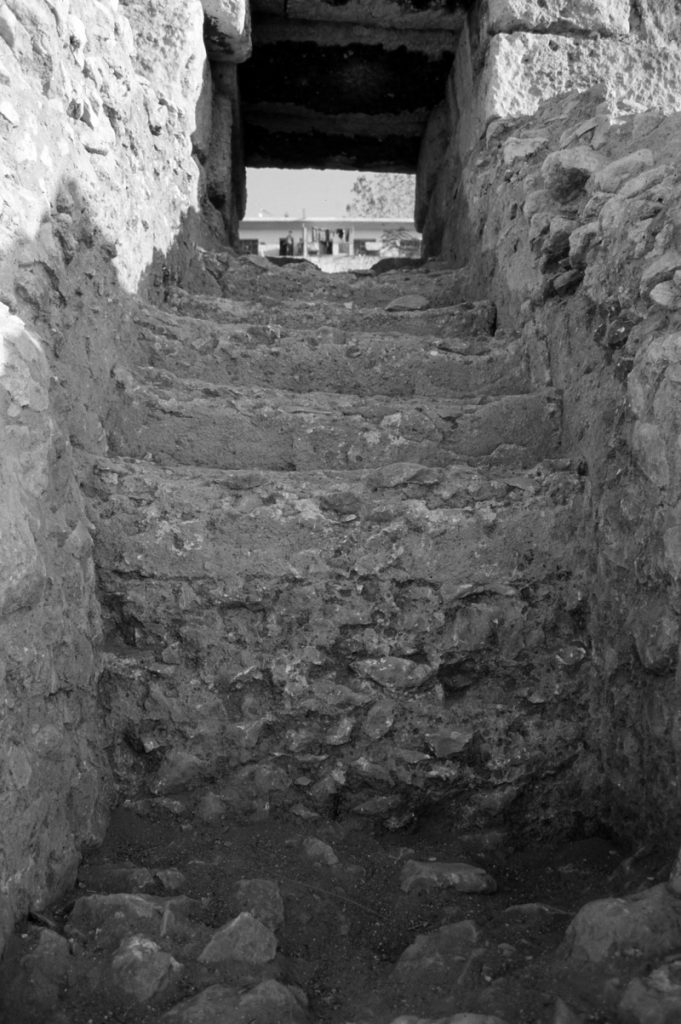

The Roman theatre of Elaiussa Sebaste, thoroughly excavated in the years 1995-1999, was built on the southern slope of the hill facing the northern harbour of the city within a major architectural project to which also the Agora and the Great Baths must be pertaining. The archaeological data leads us to date the construction of the theatre in the middle of the 2nd century AD, with an important remaking of the stage building during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. The theatre was already partially ruined at the end of the 3rd or in the first years of the 4th century, when however the cisterns to the south and the aqueduct were still in use. The complex was completely abandoned since the 5th century, and in the 7th century AD it was thoroughly pillaged, probably as a result of a well-planned operation. The excavations have also provided important information concerning the phases prior to the realization of the theatre. In the late 1st century BC and in the 1st century AD the area was at the edge of the original settlement and was used as a necropolis, as testified by several rock-cut tombs on the foot of the hill. Later, probably within the 1st century AD, the urban aqueduct running from east to west in a straight line was built about halfway up the hill. Towards the end of the 1st or at the beginning of the 2nd century AD a residential complex provided with baths was built on the same hill, but only a few rooms pertaining to this complex (that was completely destroyed for the construction of the theatre) have been preserved in the area of the east vomitorium.

A thorough reanalysis of the information provided by ancient travellers who visited Cilicia from the beginning of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century (among which Sir F. Beaufort, C. L. Irby and J. Mangles, V. Langlois, P. Trémaux, R. Heberdey and A. Wilhelm, R. Paribeni and P. Romanelli, J. Keil and A. Wilhelm, M. and M. Gough), together with unedited data coming from the archives of the Kleinasiatische Kommission der Wiener Akademie der Wissenschaften (Wien), from G.L. Bell’s Archive (Newcastle upon Tyne), and from the archives of British Institute at Ankara help us in analysing the recent history of the monument. All these descriptions and the first photographs of the theatre taken in 1905 by G. L. Bell show a quite damaged building, devoid of any important piece of decoration and of all the seats, but better preserved on the alae. Concerning more specifically the overall layout of the theatre, it has a plan larger than a half circle with an overall diameter of 55 m. Most of the cavea, which is divided into five cunei by six scalaria, was created by cutting the natural bedrock. Only the summa cavea and the peripheral alae are built using concrete, faced with ashlar blocks in the analemmata and in the enclosing external wall. A middle praecinctio divides the auditorium into the ima cavea with fifteen rows of seats and summa cavea with only five rows; above the praecinctio runs the channel of the aqueduct, following a curved route after having been deviated when the cavea was built. The entrance to the spectacle building was granted by two asymmetrical vomitoria and by two uncovered parodoi. In proximity of the western vomitorium lies the circular castellum aquae, that remained in use, as recent researches (2006) have demonstrated, until the 5th century AD, therefore after the theatre itself was abandoned.

Scarica l’articolo completo:

Scarica l’articolo completo: